Guide

From the triangle to the cube

Contents

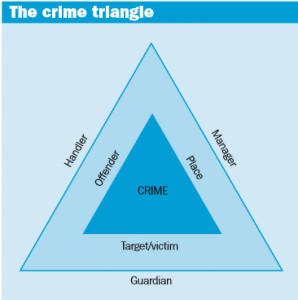

The static dimension of traditional SCP models is well expressed by the image of the “crime triangle” (also known as the problem analysis triangle) derived from the routine activity theory formulated by Lawrence Cohen and Marcus Felson. This model states that

predatory crime occurs when a likely offender and suitable target come together in time and space, without a capable guardian present. It takes the existence of a likely offender for granted since normal human greed and selfishness are sufficient explanations of criminal motivation. It makes no distinction between a human victim and an inanimate target since both can meet the offender’s purpose. And it defines a capable guardian in terms of both human actors and security devices. (Ronald Clarke and John Eck 2003, step 9)

|

In the figure the three sides represent offenders, targets and locations, or place. The triangle was an important innovation for POP policing, because introduced the exploration of a broader range of preventive solutions in addition to the traditional practices based on identification and arrest of offenders. Moreover, the triangle introduced into the policing practice new concepts, such as the analytical tool WOLF, DUCK and DEN[1]. |

In the TAKEDOWN project, the Cube is the evolution of the Triangle, built and developed with the aim of responding to events like CHEERS in a dynamic and interactive way. The Cube starts off with two initial dimensions:

- Environments, which regulate the targets available, the activities in which people can operate and who has differentiated responsibility at the location.

- Behaviours which help pinpoint important aspects of harm, intent, and offender–target relationships.

Therefore, the Cube Model is a tool which produces case-based scenarios:

A Case-based virtual Environment for CHEERS events, since the environment in which the event occurs in some way determines the roles of the actors involved and their specific ‘weights’ with respect to the instruments available. For example, if the phenomenon occurs in a prison, it is clear that the role and the ‘weight’ of the judiciary will be greater than that of external school teachers or psychiatrists, who also operate inside the prison. Within a school, however, the weight of the same teachers will be totally different, even with respect to magistrates, who may also become stakeholders in that specific context.

Multidisciplinary because it allows for the combination of various crime prevention disciplines applicable both to terrorism and organised crime, both to individuals and networks (more than one). The Cube uses a variety of causal models to achieve its crime-reduction goal and it also adds to, and qualifies, some of the major theoretical approaches of other disciplines, like the Classical School and Deterrence Theory (Cozens, 2008; Jeffrey & Zahm, 1993), Social Structure Theories (Wilson and Kelling, 1982, or the behaviourists, and SCP, all framed within the specificity in terms of locations and typology of crime.

Multidimensional because it allows for the observation, navigation and manipulation of various events and scenarios by different observers depending on the roles played by the stakeholders and the first-line practitioners, according to the various prevention tools available. A multidimensional analysis is used to examine multiple variables simultaneously in order to determine the relationships between them. Unlike bivariate analysis where there is one dependent variable and one independent variable, multidimensional analysis has more than one independent variable (Babbie, 2010). Thus, rather than explaining variations in the dependent variable as a result of changes in a single independent variable, multidimensional analysis explains the variations in the dependent variable as a result of multiple independent variables.

Multi-agency since it allows for the creation of variable and interconnected series of virtual and real scenarios in which the various actors operate interchangeably. They will consequently have different ‘weights’ depending on their institutional or para-institutional roles.

Up-scalable and Flexible: because it allows us to simulate different scenarios, analysed by different observers, according to the perspectives of observers themselves, their agendas and interests, as well as their powers and roles in real and virtual space, in relation to the general interplay. Each time the variables are changed, the scenario of the sub-systems involved changes, and therefore must be adjusted. As changes affect the environment, the stakeholders and first-line practitioners involved and the prevention tools according to the availability of the various actors, the scenario or scenarios will produce new effects on the complex and overall system.

The so-called C.I.A. models, a community impact assessment used in Britain, provides a valid example. By applying a multi-systemic logical approach to individual environments (e.g. a prison is described as a subset of communities), the impacts of decisions on various communities are assessed, be they local, near or global in extent, both internal and external to the prison itself. The same problem can be seen from multiple perspectives (that of the prison director, the prisoners, the educators, intelligence forces, etc.). This, of course, introduces actors who far more complex than those directly involved, such as the role of inmates’ families, the detention communities, the external local communities in proximity to detainees, the media, etc.

[1] The crime triangle is the basis for the SCP threefold analytic tool WOLF-DUCK-DEN: 1. Repeat offending problems involve offenders attacking different targets at different places. These are ravenous WOLF problems. An armed robber who attacks a series of different post offices is an example of a pure wolf problem. 2. Repeat victimization problems involve victims repeatedly attacked by different offenders. These are sitting DUCK problems. Taxi drivers repeatedly robbed in different locations by different people is an example of a pure duck problem. 3. Repeat location problems involve different offenders and different targets interacting at the same place. These are DEN of iniquity problems or hot spots. A drinking establishment that has many fights, but always among different people, is an example of a pure den problem. See John Eck, Police Problems: The Complexity of Problem Theory, Research and Evaluation. In Problem Oriented Policing: From Innovation to Mainstream. Crime Prevention Studies, vol. 15, edited by Johannes Knutsson. Monsey, New York: Criminal Justice Press (and Willan Publishing, UK), 2003