Guide

A new way to say CHEERS: In which cases should the cube be used?

Contents

In recent years, we have been inundated with analyses concerning the ideas of the perpetrators and the profiles of individuals and communities. Thousands of pages have been dedicated to Muslims, Christians, extremists, radicals, immigrants, ‘delinquent types’ and other such matters. Entire communities and social groups have come under the scrutiny of intelligence agencies and police forces, with the result that large sections of the population have lost confidence in states and supranational institutions and have been driven to various forms of escalation and protests. We have reached the point where the greatest activity of social media is precisely profiling and its use in mass surveillance. In this mix, media and politicians have built careers, collected resources and acquired power.

So let us affirm right away that the ‘Cube’ model only analyses real problems, i.e. it is a neutral security tool. Cases to be analysed by the ‘Cube’ are comparable and recurring according to the scheme defined by the acronym ‘CHEERS’, which considers six elements to define a problem as part of the ‘Cube’ exercises: Community; Harm; Expectation; Events; Recurring; and Similarity.

- Community are problems experienced by the ‘public’, that’s to say a stratification of different sub-groups (or sub-communities) composed of individuals, majorities and minorities, businesses, government agencies, parties, and other groups.

- In order to be part of the exercise, an event must impact members of the public, cause Harm to the whole community or part of it. We deal with serious crimes as part of the violations of the law, and legality, including legal preventive measures, is a defining characteristic of problems, unlike contemporary SCP methods (Clarke and Eck, 2003).

- Expectations concern what the community (or a large part of its members) expects from the security system to do to address the causes of the harm.

- Events refer to a chain of security incidents classified as ‘serious crimes’ as defined by the Palermo Convention and the Directive (EU) 2017/541.

- Recurring implies that similar incidents must recur in similar environments. They may be symptoms of an acute or a chronic problem. Whether acute or chronic, unless something is done, these events will continue to occur and for this reason prevention is a key. If recurrence is not anticipated, problem solving may not be necessary.

- Similarity means that the events are similar or related. They may all be committed by the same person, happen to the same type of victim, occur in the same types of locations, take place in similar circumstances, involve the same type of weapon, or have one or more other factors in common. Without common features, we have a random collection of events instead of a Cube problem. With common features, we have a pattern of events. Crime and disorder patterns are often symptoms of problems.

Motivations as part of the rational theory

In addition to the traditional CHEERS model in SCP, we must introduce new analytical factors if we want to grasp the character of the new forms of ‘serious crime’, especially in the area of ’pre-crime’ prevention.

This leads us to introduce the motivations theme into the ‘Cube’ variables, what drives certain acts as situational contributions rather than profiling, together with ‘readiness’, two substantially new components that render the Cube dynamic.

Indeed, the premise of terrorism is defined by the recent Directive (EU) 2017/541:

namely to seriously intimidate a population, to unduly compel a government or an international organisation to perform or abstain from performing any act, or to seriously destabilise or destroy the fundamental political, constitutional, economic or social structures of a country or an international organisation. The threat to commit such intentional acts should also be considered to be a terrorist offence when it is established, on the basis of objective circumstances, that such threat was made with any such terrorist aim. By contrast, acts aiming, for example, to compel a government to perform or abstain from performing any act, without however being included in the exhaustive list of serious crimes, are not considered to be terrorist offences in accordance with this Directive.[1]

For serious and organized crime the Palermo Convention set 3 fundamental criteria to define a vast array of crime types, where the scope of obtaining material benefits is at the core:

(a) “Organized criminal group” shall mean a structured group of three or

more persons, existing for a period of time and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes or offences established in accordance with this Convention, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit;

(b) “Serious crime” shall mean conduct constituting an offence punishable

by a maximum deprivation of liberty of at least four years or a more serious penalty;

(c) “Structured group” shall mean a group that is not randomly formed for

the immediate commission of an offence and that does not need to have formally defined roles for its members, continuity of its membership or a developed structure.[2]

The declared aims are therefore the element of greatest difference between the two phenomena, often also beyond basic phenomenology or logistics which, in certain temporal phases and geographical areas, can supplement each other.

But there is a true difference between goals and motivations. On the one hand, in fact, a crime of terrorism, in its execution, can be assimilated to forms of organised crime; according to its purposes, however, it can take on different meanings (and consequently invoke opposing harm reduction strategies). Finally, both can have common primary motivations, beyond declared aims. For example, both in the cases of political terrorism and mafia-like organised crimes, there may be common motivations such as the control of tangible and intangible resources, elements of territorial power or the control of political systems, but with different or possibly conflicting purposes, of a strategic or tactical nature.

In many cases, also recently, terrorist groups have tried to use organised crime logistics to procure weapons or resources of various kinds. In the most extreme cases, such as those of terrorism in Italy between the 1970s and the 1980s, actual common actions took place, such as the ‘Banda della Magliana’ and NAR groups sharing common weapons arsenals. In any case, given the difference in goals between the various criminal phenomena, the police succeeded in defeating terrorist groups by exploiting the vulnerabilities of those criminals. The pressure of the police actions can, in fact, determine a conflict between the goals of organised crime and terrorism. The ability to act on the various final motivations of certain actors in the criminal sphere is one of the main reasons why the analysis of motivations is to be considered an instrument of prevention.

For this reason motivations have quickly become an important element of SCP in the last decade, beyond the problems of profiling.

|

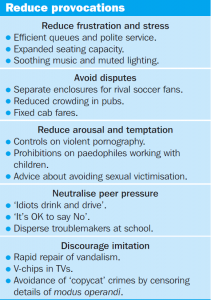

When studying prisons and pubs, Richard Wortley noticed that crowding, discomfort and rude treatment provoked violence in both settings. This led him to argue that situational prevention had focused too exclusively on opportunities for crime and had neglected features of the situation that precipitate or induce crime. As a result of his work, Clarke and Cornish have included five techniques to reduce what they called ‘provocations’ in their new classification of situational techniques.[3] These factors are very relevant for prevention |

The introduction of ‘ideological’ themes within the traditional situational prevention model has, however, created some confusion, especially when narratives (ideas, religions, political positions) have been confused with the ‘motivations’ underlying rational theory. With this confusion, situational prevention models have repeated the errors of socio-psychological prevention, frequently evolving into Terrorism Crime Prevention, which is the latest version of the surveillance systems. In reality, the narratives, in addition to being easily interchangeable, are also common to criminals and to simple opponents or innocent citizens with clean records. So, by working on profiling and focusing on the perpetrators, the risk is that of clashing against some fundamental rights, in addition to not grasping the dynamics of criminal phenomena, which are rooted in the environment rather than in the perpetrators.

As we have seen above, one of the major criticisms against the British ‘Prevent’ strategy is precisely this, having adopted psychological models as part of the mass surveillance that had been tested inside prisons for studying criminals, but which were then applied in mass surveillance programmes in order to pursue ‘population change’ and then expecting to screen ‘High Risk Offenders’ on the basis of ideas, belief systems and opinions. These policies have led to an increase in criminal phenomena, rather than to their reduction, since they have set in motion ‘defiance‘ reactions on a large scale among the ‘suspect’ communities.

The most recent STP seems to have fallen into the error of previous sociological and psychological prevention models, when it included ‘cognitive prerequisites’ among the ‘proximal factors for crime’ in the analysis of omissive and violence-free criminals and posed the problem of ‘neutralising’ ideas and feelings of opposition (Belli & Freilich, 2009, pgs. 188-189 on tax protesters). In essence, by evolving into STP, it adopted ‘conveyor belt’ theories bearing a strong ideological content, which become a criminogenic factor, rather than a preventive and protective one.

In reality, these current preventive theories are of little help in dealing with crime in the real world because they tend to find causes in distant factors related to the profile of the offenders, such as childrearing practices, genetic makeup, ideologies, faiths, and psychological or social processes. These are mostly beyond the reach of everyday practice, necessitate risky ideological constructions on ‘risk indicators’ connected to the single (or group) personality and expose policing activities to the risk of infringing fundamental rights and International conventions. Finally the force neutral institutions to become propagandists of the temporary governments.

For this very specific reason, which has important technical and juridical consequences, the ‘Cube’ maintains the basic preventive structure of the classical SCP process, refusing the SPT extension, but framing the motivations and the consequent ‘soft preventive techniques’ within a different new innovative and dynamic model.

Within the ‘Cube’ model, ideologies, beliefs and ideas are part of a dynamic and environmental interplay and are not considered ‘root causes’.

|

These highly sensitive factors are specifically connected to specific situations, and are not considered as generators of crime. Motivations are multi-semantic, situationally and temporally connected and for this reason this type of ‘indicators’ can be manipulated by all competing parties.

|

|

“Thus if you are Chinese the biggest threat right now is Tibetan, Uighur and other nationalists. If you are in Iraq it is religion (sectarianism is a much bigger danger that insurgency). If you are in Spain or Sri Lanka or Turkey, it’s breakaway nationalism. (…) Some of the founder of Israel, including a future prime minister Menachem Begin, violently subverted a League of Nations mandate and blew up the King David hotel in Jerusalem killing over 90 people. It would be today’s equivalent of killing UN peacekeepers. Moreover these were the guys who killed well over 100 Arabs, mostly old men, women and children, in the notorious Deir Yassin massacre. But it’s not just Israelis who are hypocrites. We all are. In truth terrorism is what other do, never what we do. Perhaps that’s the only defining characteristic. That’s why America sees Islamic fundamentalists as part of the Axis of Evil, and why they in turn see America as the Great Satan (..) And we need to admit that our attitudes change when terrorist win. (…) Nelson Mandela, for decades listed by the U.S. as a terrorist, became president of South Africa, Nobel peace prize-winner, and perhaps the most feted man on Earth. Moreover our attitudes change when terrorism affects us personally, rather than someone far away. As a British citizen I’am acutely aware of how many Americans, with a nod and a wink from the U.S. government, gave money- million of dollars- to the Irish Republican Army. Are our memories so short? Are our morals so shallo or our definitions of terrorism so flexible? Apparently they are.” (Ross, 2009, pg. 232)

Similar fluid cases could be described for the cooperation between mafia and national or international politics in Italy, starting from the WWII and the role of the American Mafia in the liberation of Sicily.

All attempts to transform these ideological elements into security techniques quickly morphed into purely political or manipulative operations by one of the actors involved. Therefore their use became ambivalent: they could be protective elements, but they could also constitute a further risk escalation factor, as we shall soon see when analysing the stakeholders.

The motivations are relative. What counts is how the various actors perceive them with respect to the rational choice theory, which from the beginning envisaged the assessment of dynamic irrational rationality processes (‘limited’ or ‘bounded’ rationality) for prevention actions and this is precisely what constitutes the basis of the ‘Cube Model’:

“offenders behave in situations (physical and social environmental settings) according to the ways in which they perceive them. They perceive their own needs (they want money for a drug habit), and they perceive environments (near and far) as offering them opportunities to carry out their course of action, whether it be burglary, bank robbery, or a terrorist attack. Why offenders choose to commit crime as a means to get money rather than get a job is the question unanswered by rational choice theory. Or at least is seen as less relevant than the question why the offender chooses burglary instead of bank robbery, or why the terrorist chooses to bomb a building instead of hijack an airplane. It is offenders’ perceptions of both opportunities and constraints that condition their course of action. To the outsider or observer of their behavior, the courses of action taken by offenders may or may not appear rational. To the offender, the behavior is perceived as a rational way of achieving an end.” (Freilich and Newman)

Seen in this light, the phenomena of terrorism and organised crime bear a certain teleological level of ‘rationality’ and ‘agency’, even when they appear to the external observer to be completely illogical or devoid of purpose, if the reasons that support their perpetrators justify the expectations of the individual.

The apparent illogicality of a suicide bomber actually masks the logical search for a superior “good” to which he/she somehow consciously or unconsciously aspires (Becker, 1968, Tilley, 1997, pp. 95-107; Newman, 1997, p. 21). The difference between consciousness and unconsciousness exactly corresponds to that between narratives and motivations, which is a central distinction to understand what we mean by ‘motivated perpetrator’.

Indeed, there is a substantial difference between motivations and narratives which justify acts at a given moment. What matters is how the parties involved use them: governmental power can use them to gain consent for their own security policies; perpetrators, on the contrary, to justify criminal actions judged immoral by most. Narratives, on which profiling often focuses (Muslims, Christians, extremists, radicals, etc.), can be temporarily adopted to justify or motivate a completely different nature or simply to attract attention, based on emulation mechanisms whose motivations coincide with primary needs. In other cases, narratives are used to provoke whoever is seen as an enemy and in yet other cases, to forge alliances and garner support, as often happens in prisons or on the international political scene. Also recently, many Middle Eastern regimes (keeping the discussion at those latitudes) have exploited security narratives to justify wars or dictatorships.

Therefore, focusing too much on the declared narratives with respect to the motivations that are at the basis of the ‘rational theory’ is likely to lead us completely astray, because often the flaunted narratives are nothing more than artificially adopted ‘provocations’ or ‘justifications’. We must never forget that chasing the ‘conveyor belts’ or the ‘clashes of civilisations’ too closely, as well as being counterproductive, risks being totally ineffective.

Though the link between violent movies and violence in society is much disputed, there is some evidence of ‘copycat’ crimes because media reports of unusual crimes sometimes provoke imitation elsewhere. It has also been shown, for example, that students who see their teachers engaging in illegal computer activity are more likely to commit computer crimes themselves, and that other pedestrians will follow someone crossing against a red light.

On 27 December 1996, Maria Letizia Berdini was killed by a rock thrown from a highway flyover near Tortona in Italy. The news got a certain amount of coverage in the press and since then stones thrown from overpasses have multiplied in emulation events: 63 cases were recorded up to 31 August 2017 and an actual total of 85 in 2016, almost one every 4 days.

However, the Italian police noted a cyclical pattern in these phenomena linked to geographical, information-related and territorial factors, albeit acknowledging the substantial heterogeneity of the perpetrators and the reasons they claimed to justify their acts.

Hence, the motivations, filtered of all ideological aspects, become translated into a set of correlations related to the criminal process and described as such in simulations.

Assess the Readiness

In this fluid context, the link between prevention and crime is developed by the SCP approach through the introduction of ‘readiness’ parameters, an analytical category that can be adapted to almost all prevention models.

Also this category is prone to confusion, since ‘readiness’ is one of the mass profiling indicators in the ‘Mappa‘ strategy adopted by the English Home Office and other intelligence agencies.

Traditionally, the ‘readiness’ of individuals and groups is expressed according to three levels, often accompanied by coloured visual maps:

1. Individuals ready to commit crimes almost without their being aware of it. These include environmental cues that may provoke or prompt individuals to action (Wortley, 1997, p. 66).

2. “Distal factors” which place individuals in different states of readiness (Wortley, 2011), and potentially more responsive to opportunity factors leading individuals and groups towards a higher propensity to commit crime (Tilley, 1997, pp. 95–107).

3. Individuals operating at a conscious state of readiness as a result of evaluating alternative means of meeting a perceived need, including revenging real or perceived grievances, and this conscious state is impacted by a host of background and situational factors (Cornish & Clarke, 1986, p. 3).

Recently, Canadian intelligence has developed a ‘readiness’ analysis model based on HOW crimes are prepared, rather than on WHY they are committed[4]:

“For example, in an attack planning scenario, indicators of mobilization to violence may include purchasing supplies, reconnoitring a target or recording a martyrdom video. It is important to note that a low-tech terrorist attack may require nothing more than a knife or a car. This type of attack is especially difficult to anticipate, but indicators are often present, even in the simplest of terrorist attacks.

A person preparing to mobilize to violence may also wish to conceal their activities from authorities or from the people around them. In that case, indicators of concealment and deceit could appear. For example, the person may use software to encrypt their communications, invent a cover story to justify their departure from Canada or create an alter ego.” (CSIC, 2018)

So, in our event management view, ‘readiness’ is clearly in the HOW category of criminal path descriptors and precisely identifies various types of crime. In this sense, it is a factor that profoundly differs from those identified in the ‘conveyor belt’ theories centred on psycho-ideological precepts.

Following the different risk assessment models present in Europe, ‘readiness’ and ‘motivation’, in the Cube Toolkits framework, are correlations applied to all actors, not just to perpetrators. In particular, ‘readiness’ is a very important correlating element with regard to preventive actions in the pre-crime context.

[1] Recital 8 of the Directive

[2] United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, art. 2

[3] Richard Wortley, A Classification of Techniques for Controlling Situational Precipitators of Crime, Security Journal, 14: 63–82, 2011

[4] Canada Security Intelligence Service, MOBILIZATION TO VIOLENCE (TERRORISM) RESEARCH, key findings, 2018